War Memorial Chapel

Click on the links below to read the text:

The Chapel Complete (Video clip 1958)

The Move to Yorkshire

In the summer of 1940, with the Battle of Britain pending, John Bunting was evacuated from school in Ramsgate, Kent to Ampleforth College. Whilst at Ampleforth he became familiar with the furniture distinguished by its mouse trade mark and produced in Kilburn, by Robert Thompson. It was not long before Bunting found his way to the workshops in Kilburn, where Mr Thompson taught the youngster how to carve. Leaving Ampleforth in 1945, Bunting was enlisted in the Royal Marines. What follows is his own story.

When 1947 drew to an end I was demobilised, given a suit, some leave and £60 and returned home to start work. There were opportunities in the City, in the Tea Trade. I visited Plantation House, Simpson's Cornhill, the Jamaica Inn. My father knew the City well and every bar and usually knew the people. There was a lot of drinking, some excellent meals, tossing coins for bottles of port. The narrow alley ways along which we sped were cold and seldom received sunlight. The offices were permanently illuminated. At the end of the day there was the hour long tube ride to Barnet or Amos Grove and the subsequent wait for a bus or taxi. After some such occasions I came to the conclusion it was not the life for me.

Robert Thompson wanted me to return to Kilburn and offered me £5 a week. My sister Angela accompanied me to Kings Cross to catch the train North. The sky was dark grey - unnaturally so for a thunderstorm threatened, as though marking the occasion as one of decision and gloom, though I was not to know then what a decisive step I had taken. And so began the long journey north to a village where I would be regarded as a stranger and where the strong Yorkshire dialect was at times like a foreign tongue to my Southern ears.

On my journey North I had time to speculate on my departure from London. I had work to look forward to, work which I liked and in a place with which I was familiar, in countryside I knew and liked. The City and its life style did not attract me. There seemed at least a possibility that Kilburn might be a feasible alternative. Kilburn offered an opportunity and reasonable scope of interests, in addition I was being invited to work there and I was glad to accept.

I moved into the Fauconberg Arms Hotel in Coxwold where I was cared for and well fed for the three months till Easter. Each morning I walked into Kilburn to start work at 8 o'clock. In the evening a bus took me back to Coxwold when there was time for a hot meal then another bus came to take me back to Kilburn where I worked for two more hours on my own carving. I soon had a number of small carvings finished. When Easter came I moved to Reg Shipley's farm half-way to Kilburn from Coxwold. At Easter I went home and on a walk in Hertfordshire I called at Much Hadham to see Henry Moore and he showed me his workshop and sculpture - the Madonna for Claydon was nearly finished. He advised me to go to art school and learn to draw and get a teaching qualification to be able to eam a living.

I returned to Kilburn to finish my year of work. Life at Kilburn was unruffled and hard working as summer moved to autumn and into winter and I knew I would soon be back in London. Kilburn village when I knew it in 1941, in 1945 and in 1948 had hardly changed its way of life since the beginning of the century. Horses were still used and there was a blacksmith. Most villagers kept a pig for ham and bacon. Milk was delivered from a churn and measured by the imperial pint. There was a butcher and an inn. Beer was drawn by a white jug from wooden barrels. The church had a Norman arch and Kilburn Hall after the Conquest became a hunting lodge of the Archbishop of Rouen. There were remains of a Roman road. A lively stream of water ran beside the road through the length of the village.

The village lay below the high escarpment of Sutton Bank at the meeting between the Vale of Pickering and the Vale of York. The people in the village grew most of the food they required. They made their own butter and baked their own bread. There was a market nearby at Thirsk for the sale or purchase of items that could not be supplied in the village. Life was slow and steady and generally long-lived. There was a completeness and sense of fulfilment and content which contrasted with life in London or the northern suburbs. I was able to glimpse all this and to share in the life of the village before all vanished in the 1950's.

When the year of 1948 came to an end I knew I was leaving something strong and precious. Fred Suffield called for me to take me to Coxwold station. We went through Kilburn and Oldstead and over the hill to Coxwold. There was a heavy December frost and rime lay on the cobwebs that festooned the hedges. It was a crisp morning of cold air and pale blue sky silhouetting the line of the moors around Sutton Bank. I knew I had to leave. But one day I hoped I would return, and, if possible, earn my living there or nearby. In seven years this wish was granted in a way I could never have foreseen.

Building the Chapel

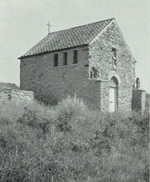

On the promontory of a hill overlooking Oldstead and not far from Kilburn and Coxwold, upon Forestry Commission Land, were the ruins of a farmstead now rebuilt by the sculptor John Bunting, as a memorial for those killed in the 1939-45 war. The position of the chapel could not be bettered. In front, the hillside drops away sharply to a wooded valley and in the distance can be seen York Minster. The buildings stand on a piece of flat land butting into the side of the hill just below the crest. Beyond the crest to the North and the East , stretch the Yorkshire Moors; away to the West, across the Vale of York, lies the Pennine Range.

Bunting first visited the site in the summer of 1941. The buildings were roofless and, in such an exposed position, most of the walls had crumbled. In 1956 Bunting acquired the derelict site and began renovating the buildings. The larger of the two he chose for the chapel and in 1957 he commenced excavating the rubble. When the floor-level was clear he collected a heap of building lime mortar from the inside walls and after this, building of the south wall began. Cement and sand could be delivered to the site by lorry. For a time there was sufficient water for mixing the cement in a dewpond in the heather.

When the wall reached a height of six feet, scaffolding poles were needed, (also planning permission!) Plans were drawn out for approval and a local timber merchant delivered some straight larch poles and planks as a scaffold. Bunting was told of a mason who might assist him in the work. Mr. Winspear from Oswaldkirk subsequently helped him and with this accelerated progress, the water supply was soon exhausted. Thereafter they took 15 gallons of water each day in the back of his Alvis.

An arched doorway surmounted by a narrow rectangular niche in the south wall were built; in the west wall three small oblong windows were constructed. The weather was kind although it was late autumn. Soon the ‘pans’ and ‘wall plates’ were set and they began work on the windswept gable ends. In early December the joiner put the roof timbers in place and they tiled the roof with some pan tiles brought from a local cottage that was being demolished. When the last pantile was in place it began raining and the rain water again trickled off rooftiles as it had done fifty years before instead of soaking into the ruined fabric. Shortly before Christmas the entrance was boarded up for winter.

While the winter months lasted, work began on carvings intended for the chapel. First, John Bunting carved, in York stone, two angels, each carrying a scroll - one inscribed 'Glory to God on high'; the other 'Peace on earth to those who seek it', using the Latin text. These angels stood on flanking projections outside the chapel (until stolen in the mid 80’s). For the arched doorway, resting upon an oak lintel, also in York stone, he carved the head and shoulders of a man stretching up towards a dove with a sprig of olive in its beak; for the niche above the door a Madonna and Child.

Then he cut three inscriptions: two in Hoptonwood stone and one in white marble. The first of these is in memory of Hugh Dormer. Dormer, like the other two commemorated, was educated at Ampleforth College, later at Oxford. At the outbreak of war he joined the Irish Guards. During the preparations for the invasion of Europe, Dormer joined Special Operations Executive and was twice parachuted into occupied France to destroy war plant, returning over the Pyrenees to England. For these services he was awarded a D.S.O. He rejoined the Guards Armoured Brigade and was killed during the battle of Europe in 1944, aged 27. The 'Diaries' he kept of his parachute missions and the final decision to return to his battalion were published posthumously by Jonathan Cape.

The next inscription in Hoptonwood is in memory of Michael Fenwick, a poet, killed in 1941 at Kowloon aged 21. A collection of his verse was published posthumously by Blackwell, at Oxford. The last inscription, in marble, is in memory of Michael Allmand, founder of the literary review, ‘The Wind and the Rain’, who was killed in Europe in 1944 aged 23. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for heroic gallantry.

Although the chapel commemorates all those who died in the war, in particular it commemorates these three young men. And of these three, Hugh Dormer is foremost. Because of this the central sculpture inside the chapel is of a recumbent soldier wearing a paratrooper's helmet and Commando boots.

The floor is covered with stone flags and the three windows fitted with stained glass designed by the artist. At the soldiers head is built a rough stone altar and above this the sculptor carved a wooden crucifix in memory of those who died - and as a reminder too of the peace they died to bring.

The site of the chapel is where the Battle of Byland took place between the English, led by Edward II, and the Scots in 1322 - a battle in which the English were routed. Tradition has recorded this event by referring to the site as Scots Corner. Nearby there are two burial mounds of the Bronze Age.

The Chapel complete - Video

On Carving a Crucifix

In 1953 Bunting won a travelling scholarship to Spain. What follows is his description of carving the crucifix which hangs today on the East wall of the Chapel.

Whilst I stayed in Seville, I intended to carve a crucifix assembled together from many blocks of wood held by glue, in a manner employed by Montafies and his contemporaries. The carpenters shop where the blocks of wood for the crucifix figure were being assembled, was part of an art school for junior and part time students. From time to time in London I had had work cut for me by bandsaw. These machines are heavy and because there is a danger of the metal saw breaking they are well protected. Usually I have found only one man is allowed, by trade union regulations, to operate the machine, and he has usually been very reluctant to do an odd job or to saw slightly thick pieces of wood. The contrast in this workshop was startling. They apologised for a bandsaw which was made out of odd bits of wood. It was started by swinging on one of the two big wheels - then it ran on electricity. The man who operated the bandsaw worked with a dash and recklessness that delighted me. He cut through an 18" thickness where 6" in England would be considered dangerous.

This by itself is a trivial example but the whole shop was pervaded by a similar spirit of zest and makeshift. Nothing was too difficult; no shortage couldn't be overcome; there was no tool they weren't prepared to adapt. The blocks of wood, planks, handscrews and bits and pieces that were used to adapt a planeing machine into a spindle-moulder, in the space of fifteen minutes, need to be seen to be believed. I could not help pitying them working haphazard implements with such childlike enthusiasm. I have no patience, either, for those who say Spaniards won't work. These men started work at 9 in the morning and worked until 10 o'clock at night for six days a week. Lunch was from I till 2, but whenever I called some of them were working. Most evenings there was a power cut. This is typical of the minor inconveniences that Spaniards have to put up with. Usually the electricity isn't switched on until 10 in the morning and because of this most of the work for the next morning is prepared late at night.

Apart from 3 men the rest of the workshop were boys under instruction, aged 12 - 16. As the workshop was part of an art school, I compared their system of running it with our own. The carpentry shop was run by one man and the boys who came into his shop to learn their trade learnt it thoroughly. There was none of the idleness I associate with English art schools, because the head of the shop was entitled to use the apprentices to produce work which he could sell to augment his salary. The boys made and carved superb gilt mirrors.

English art schools should adopt a similar practice. Under the present system of State art schools, there is very little discipline or hard work and there is an incredible wastage of tools and materials. A student who is keen to work and study can only do so by fighting against an oppressive atmosphere of indifference and idleness. But if the master in charge had the incentive of private profit in addition to his fixed salary, I think it would help to restore the lost atmosphere of a proper workshop. In this one, children of 12 and 14 were handling carving tools, pointing machines and mallets with greater assurance than most sixth year students in London art schools. Art schools have fewer and fewer artists teaching who know any craft other than the 'craft' of teaching. Consequently art schools 'teach art' (which can't be taught) instead of teaching them their craft and the art school spiral winds its way upwards. At the time of Montafies there was a guild exam. Beside producing a 'masterpiece', apprentice sculptors had to show a knowledge of anatomy and ability to carve drapery before they were allowed by the guild to open a workshop.

Once the blocks of wood had been glued together, using a large drawing to work from, I soon carved the figure and had it ready to be painted and gilded. The students watched me the first day to my discomfort. They used pointing machines and were interested to see how the 'Ingles' worked without a pointing machine. I was even more interested to see the result.

I worked extremely hard and in a week it was finished, but the soft wood helped me to complete it so quickly and as usual I was filled with mixed feelings of doubt and determination as to whether it was finished or not. Eventually under the instructions of the 'dorador' (that is the gilder who himself worked for a master) I gave the wood two coats of size, (a mixture of glue and water). When these were dry I gave it a first coat of gesso (slaked plaster mixed with more glue and water) which was left to dry in the breeze. I completed three coats of gesso.

On one occasion I went with the 'dorador' to visit his master's studio. It was a disused stable and four or five men worked in a confined space surrounded by parts of a large 'paso' nearly six metres in length. The carver also worked amid that confusion, and figures he had carved and which were now being painted, lay scattered round the shop in various places where they couId dry. The master assured me there was more to be learnt working in his shop than could ever be learnt in an art school - but I needed no such assurance. This was a mediaeval workshop. The sculptor fitted in alongside the other men. He was simply a man with a different job and he had made some superb crucifixes and statues in this local tradition. His fellow workers were evidently pleased and proud of him for to a large extent the reputation of the workshop depended on the sculptor's skill and imagination. The master dealt' with the clients and arranged the commissions. Each man had a part to play in this place and yet here six men worked in a space that in England would have been insufficient for one man. The 'paso' they were engaged in making cost about £3000 and every year, as the church commissioning it saved more money, so more work was done. It would take 4 or 5 years to complete.

Whilst I made preparations for gilding my crucifix there were whole days when I could do no work waiting while a coat of preparation dried. After applying three coats of gesso (which took three days) I spent two further days sand-papering the gesso till my fingers ached. Then a preparation of glue and water - very little glue and the mixture slightly warmed - had to be put on the loin cloth which was to be gilded. Care had to be taken not to allow the gesso to become too damp or it flakes off. The glue acts as a fixative. When that coat was dry I painted the loin cloth with a reddish evil-smelling mixture of very fine red earth and water. This red fluid assisted the burnishing process later on. When that was dry the wood was ready to gild.

During periods of waiting I took the opportunity to go and see other crucifixes. Near the Puerta de Carmona at San Roque is the Cristo de Fundacion which Francicso Ocampo carved some years before Montaiies began his work in Seville. There is more rhythm in Ocampo's work and he has less realism than Montaiies. It had a hint of Berruguete, the Toledan sculptor who trained under Michael Angelo. In the University Chapel Montaiies, de Mesa and Pacheco are well represented by works. There are two superb Montaiies sculptures, St. Ignatius, Francis Borgia and a retablo attributed to him; a crucifix, Cristo de Buena Muerte, by his pupil and assistant Juan de Mesa and some paintings by Pacheco. The church is mentioned by Cervantes in 'Novelas Ejemplares'

Built by John Bunting in 1957, at Scotch Corner, close to Hambleton on the edge of the North York Moors National Park. This photo was taken in 1957 - the site is now surrounded by woodland.